With the Fed already several hikes (and many billions in portfolio run-off ) down the road to policy re-alignment, it’s natural for a new Fed Chair to consider a pause for reflection. Especially with financial markets doing most of the work, tightening financial conditions and reminding both market and economic participants alike, that the cycle hasn’t been repealed. But daddy’s home.

The gravity of the situation – Apples fall.

The stock bull market almost reached 10yrs, before flirting with the “bear phase” which would have formally ended it. In fact, the bull market could with luck, reach its teens.

The Fed, like the parent, misunderstood and ignored by the teen, has suddenly gained control of the narrative. Just in time. Far from adding to volatility and market instability, the Fed now has the ear of markets and can steer, if it chooses, those markets to firmer ground. The risk of bubbles has abated somewhat – not entirely. But the risks of geo-pol have only just arrived and remain. Policy making, like parenting, is about firm and thoughtful guidance, and nurturing the offspring. With so many “teens” in markets, success is perhaps only 50/50. The ubiquitous teen-talk about bubbles, collapse, and of course distrust in the system, only enhances the risk for a parental Fed. Little wonder the Fed is in “pause” mode.

Back to the past – when the kids listened and spoke when spoken to.

Once upon a time, the Fed was an institution to be heeded, indeed feared. Then the Great financial crisis hit, and the dash to emergency policy, coupled with similar, belated moves by the other global Central Banks, left the markets with little appetite to take any real notice of the Fed. Volatility fell across all asset classes, no less, the (normalized) implied volatility built into options on short rates. It didn’t help that the Fed became laden with the debts of the US Treasury and her newly found orphans, the GSEs. Monetary and fiscal policy had to all intents and purposes merged. Markets listened intently to what the Treasury Secretary said, and in reality, ignored the Fed. And markets are always right.

Many will argue this is an affront, a falsehood, but in our opinion, apart from a brief quarter or two in 2013 (the taper tantrum), markets themselves have taken almost no notice of the Fed. For sure, Fed watchers probably quadrupled in number within money management houses, and some will have camped in the ear of CIOs. But when history writes the epitaph, it will surly read

“Here lies Sam – he was a Fed watcher all his career, and while he listened a lot, and talked even more, he heard nothing and told no one.”

They mustn’t be blamed, since, if you were paid to listen to Ben Bernanke and Janet Yellen, you’d have quickly wished you were reading Liars Poker.

The old days were fun, and the Fed lied and cheated, and were deliberately obsequious, because they could be.

The Fed ruled.

Back to the future, one hike at a time.

Last year was the year where markets took notice of the Fed, and we for sure don’t know why. Perhaps it was because finally, the Treasury had run out of fiscal road, and while the Tax bill would indeed impact the economy more than the “economisseds” initial estimates (thankfully updated to fit the actual data), the loss of the House and the loss of administration staff (think Kelly, Mattiss, etc) showed that monetary policy could now finally be of use to stabilize the economy (and therein markets).

Markets spent 2016 and 2017 growing comfortable with the Fed’s “wishful thinking” tightening.

While they talked tough, they still only managed to sneak a few hikes in amongst the “debris of the dots” at the quarterly press conferences. Instead markets focused on the “new-new normal” of geo-political change – think Brexit, Trump, Iran, North Korea, and of course China trade wars. These were a big deal, so no need to pay any attention to the Fed as they were on autopilot – raising rates, letting the balance sheet run off slowly – the proverbial “hiked and drawn-down”, a quarter at a time.

So when the geo-pol started to rock markets in earnest, the last thing anyone took any notice of was the Fed. Stocks rose throughout 2017 on the reality the Trump administration would be pro-business, and as 2018 began, the Jan/Feb “volatility-volatility” became the first test of the new Fed Chair Powells’ resolve. We wrote here, that we felt this nothing more than a correction and expected markets to make new highs once the Vix was fixed. Indeed, we were the only commentators (we saw) that felt the calamity was triggered by a good-old fashioned 80s-style spat between the EU and Mnuchin. “Geo-pol-vol” had arrived. The Fed hadn’t.

Are we there yet dad? – YES!!!

Through the summer, once markets naturally regained composure, the Fed tried (bless them) to declare victory – “the inflation target has finally been met! – rejoice”

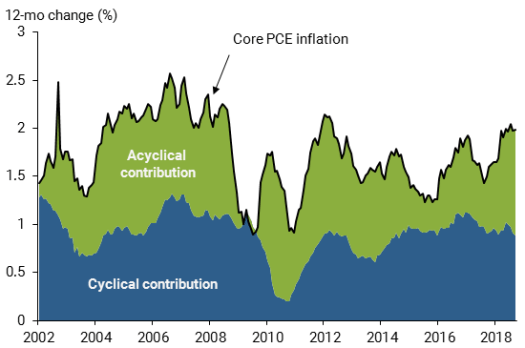

Except the target was reached through “acyclical” factors (see chart above) – Fedspeak for one-offs like cell prices etc – indeed the Phillips Curve, which would prove to be the only salvation, was still MIA.

But wage inflation continued to rise, and finally all the models that fitted vacancy and “quitting” indicators to forward expectations of wages popped, showing wages were on the up – 3%, 4% the sky was the limit.

The Fed reacted like any parent of a tone-deaf, antsy teenage bull market – it shouted – a little. No one listened.

Just you wait until Dad gets home

Then in September, “mum” shouted.

Lael Brainard, the Fed governor the previous administration planted to hold the dovish line, seemed to be talking aggressive – about perhaps a neutral “endpoint” for policy much higher than the already higher market opinion. Having seen a nice young girl in a bonnet, markets suddenly saw the old woman. Perceptions changed.

Markets perception of the Fed’s endpoint for rates, as proxied by Fed funds in 2 years time, marched higher. Having risen slowly through the year from 2.2% to 2.75%, Brainards hard words caused the rate to rise towards 3.2% by late October. Stocks, already buffeted by US/China trade tensions, could take no more, as the below charts show, Brainhard’s speech marked on both,

For sure, the subsequent Sep 17th announcement of $200bn of chinese goods to carry fresh tariffs caused uncertainty. But the march higher in 10yr Treasury yields, to 3.25% in early October was surely the reason stocks finally cracked. The continued tension on the Fed’s endpoint, which kept the 10yr yield near 3.25% until early November, maintained pressure on stocks into year-end.

Ok son, now I have your attention.

Call us crazy, but we see this episode as “good parenting”. The Fed is finally being listened to, and even if she remains on auto-pilot, the fact is she has “guided” financial conditions tighter, let air out of a potential bubble in stocks like Netflix and the FANGS and guided the major stock markets around the World to “firmer ground”

As we write today, the SP500 is at exactly the same level as it was on 29thDec 2017. 2670-ish.

For sure, credit markets are weaker. EM is still a mess. But that is all consistent with the tightening of policy that actually took place in 2018. Imagine a situation where the Fed had shaved hundreds of billions off her balance sheet (QT) and hiked 1%, and markets were ALL unchanged. Not just SP500. Yes, you know it could have been so. The fact that it isn’t is the evidence that the Fed is being taken seriously for once. The 1% tightening in 2017 actually “tightened” credit spreads. Talk about unruly teens (see chart below).

Pause for thought as conditions get “icy”

The Fed is busy signally it’s trying to pause, and is clearly back to using “forward guidance” – jargon for “talk” – to maintain the attention of the “teenage bull market”. We flagged this back here, and now it’s consensus. Nothing to see now – move along.

But the Fed senses we’re at a bend in the economic and financial cycle. This does not have to be the end of the cycle. But prolonging the cycle, by reducing the risk of either inflation, or a financial bust, will be tricky. Things are cooling off, and the temperature is dropping. It’s geting icy on the road.

Never brake on a bend.

First rule of driving fast – never brake on a bend – brake early, and steer through. This will require quick, and skillful use of the brake and the accelerator pedals. Experts call this switching between the two pedals “heel & toe”.

Going forward, the Fed will implement more “heel-&-toe” policy as it senses the cycle is on a bend. This will entail quick and quite erratic switching between the tightening “brake” and the market sympathetic “toe” pedals. This is not the same as “writing puts on the equity market”, but it will (and already has) confuse Fed-watchers and market participants.

In more formal terms, the Fed is very mindful of tightening financial conditions, especially when achieved through weaker equity markets, and that’s where the tightening will be achieved. This may result in very little actual tightening, and if any, mainly via reductions in the balance sheet (QT).

The melting of the Fed caps

The Fed has gone overboard with its attempt to not disrupt markets, as it tries to undo all the “necessary” disruption of markets that it’s quantitative easing policy has already created. The steady run-off of the balance sheet, preventing the need for physical sales, has led markets to acclimatize. That said, the reversal in “risk absorption” that the Fed achieved through its purchases, both interest rate (duration) and credit risk, is already having an impact on the credit markets, especially the emerging markets. So as the caps on redemptions of securities gradually become less important, allowing a faster run-off per month, the declining balance sheet will at the margin add to the burden on risk-markets.

And remember, the Fed’s is not the only iceberg that’s melting. Other Central Banks, most notably the ECB, will try to shrink their balance sheets this year. The combined “shrinkage” will definitely have an impact on global markets.

Wagging the finger is not the same as wielding the stick.

But before anyone gets carried away, note, as we wrote in Cracking the Code,, none of the Central banks are actually tightening policy. Indeed, we’d call it more an attempt to ‘unease’.

With US real policy rates close to zero (supposing inflation is stable at 2%) and a balance sheet close to $4 trillion, they are still “peddle to the metal” – note policy has rates lower than the real federal funds rate seen 80% of the time in the 50 years before the onset of the financial crisis in 2008. Europe, Japan, and UK are fully pedal to the metal.

Has political correctness infected Fed policy too?

So how come the Fed is pausing when it’s barely “uneasy”, let alone tight?

While the US banking system is in better shape, on profitability and solvency ratios, it’s never about conventional banking systems these days. At least first order. The GFC was about the “shadow banking system”, whose excesses and retribution fed back into the conventional banking system. No one thinks the current shadow banking is in better shape, especially the global version.

But in reality, we feel the Fed is (rightly) acknowledging the need to proceed carefully because of three genuine challenges – housing, geo-politics and the end of Libor.

As unsafe as houses – again?

We don’t have space to explore the precise challenges in the US housing market, but we would summarize them as follows. There is never one homogenous housing market. Instead one sees regional and demographic forces dominate the broader macro factors of cost and availability of finance. The latter have improved enormously since the GFC, but regulatory, and now monetary tightening, have removed their stimulatory scope.

Instead we’d suggest the housing market, if we had to call it a market, has evolved on three paths. The upper end, with extra bedrooms and big yards, boomed. The middle market, with “just enough bedrooms” for the kids, improved slightly, while the lower end of the market, call them apartments, largely stagnated in real terms.

We acknowledged that no “approximation”, least of all the cartoon variety, would suffice. But using this break down, what we’re now seeing is re-attachment of the three segments. The upper end is declining, while the lower end is finally rallying. The middle is still moderately improving, but with regional influence.

The simple reason for this – demographics, combined with (enhanced by?) tax policy. As the boomers and their later cohorts retire, the “extra bedroom” becomes unnecessary. Affordability for the middle-segment house owners is challenged, partly by the new administrations tax policy, and the result is this re-attachment.

While this is not now a housing crash, and doesn’t have to become one, it may yet result in one.

But as the last crisis was sponsored by housing, the Fed would be prudent to take care this time around.

The neighbors’ kids are as unruly as ours.

The second challenge the Fed faces is geo-pol – the threats and challenges that emanate from the neighbors. They face similar problems, whether China or Europe, and again the Fed has learned from the systemic nature of the European sovereign debt crisis and China’s “stumble” in 2016.

Death to the ‘ibors

And so to the third challenge the Fed faces.

Remember, the global monetary system remains one where the dollar is primary, and credit is administered using Libor, and it’s relatives (the “ibors”) to value risks and apportion return. Little wonder that Fed policy has had an impact, especially in the emerging markets (EM) debacle in 2018. While many have pointed to the decline in (various versions of) global M1 money supply, we are more concerned about the pullback in global lending.

Of itself this would be enough to sound an alarm, given the connectivity of global finance. But since August 2017, when the UK governing body for Libor announced its certain demise (see here), the Fed has been preoccupied with what will take its (their) place. No less than the very reform of the global monetary system, the US and therefore the Fed, will want to remain at its very heart. Rather than dwell further here, we will explore this complex topic in a forthcoming post. But suffice to say, a Fed that was already finding it impossible to breathe life back into its beloved (and unsecured) “Fed Funds” looks to have deserted it in favor of a move to the fully collateralized SOFR system. In short, this looks to us to ensure more volatility in short rates and more “connectivity” between term premia (long end and short end of bond markets) via government repo, than we saw in the past with money rates reflected in “wet finger in air” bank submissions of Libor. As the Fed relinquishes some control over longer bond yields (via QT), expect a more formal link between Fed”short rates” and longer bond yields.

This will give Fed “rate and QT policy” much more traction, albeit erratically at first – like driving on ice – and result in the need to take care, as the “brake and gears” will have a very different feel, as the system offers more traction to Fed policy.

But the twin effect of global CBs “uneasing” and “ibor-reform” is that the growing squeeze in global liquidity will become a greater headwind for financial markets.

All we have to fear is the fearmongers.

So with all that, it’s surprising markets didn’t crash when the Fed talked aggressive in September. The fact that they instead “re-priced”, offers encouragement that the Fed is in more control, not less, and the markets have sufficient liquidity to remain functioning. That didn’t’ stop the usual suspects reaching for their “bubble of bubbles” charts and technical analysis that proves the sky will fall exactly 0.38 % from the ichimoku clouds, etc. Some even reached for conspiracy theories about Rothschilds.

They had their day, and now they are having their humble pie.

Fed up?

So, to conclude, we feel the Fed will remain Reactive this year. The “talk” or guidance, seems to be working well, and while some (just like the teenager) will complain that the Fed is confusing and babbling, the reality will be that markets will begin to enjoy the parenting.

Chop Chop.

That should, all other things equal, allow markets to continue to repair. We have expected the recovery in markets thus far, and continue to expect further squeezing of the shorts. That may actually transpire in another year with negligible (if positive) total return. The bend in the cycle, unless it marks the point of collapse, often occupies moderate returns, before markets power on. Of course, we should expect volatility, in the form of ups and downs, to become the norm.

And as important as the Fed will be this year, perhaps the bigger event should be the end of ECB’s Draghi – and the choice of his successor. Perhaps, even the out-performance of non-US markets that looks so likely, will also prove frustrating.

Either way, both longs and shorts should sleep little and could lose lots.

Time for a change?

One thing we feel fairly confident of, and is far from consensus currently, is the need for the Fed to provide a new mantra for it’s decisions. With the new chair Jay Powell clearly less enamored with the regressions and models of the old guards, one would expect a new mechanism to look more “common sense”.

We have long argued the only logical basis for “inflation targeting” can be that of “Price Level Targeting”, by which we mean policy that is aimed at making sure the (average) price level (in the economy) rises consistent with a 2% pa rise over the longer term. In essence, that means that, if the Fed misses the objective (2% pa) in one year, it has to allow more inflation the following year, to average 2% over the following years.

Given the Fed has missed (below) its target most of the time since the crisis, it has an awful lot of making up to do. This mantra would justify remaining “easy”, at least in terms of zero real policy rates and a huge balance sheet, for quite some time to come.

So we were encouraged to see the new FRB of New York President John Williams argue that such a framework, of average-inflation targeting or price-level targeting, could guard against too-low inflation expectations taking hold.

And before one asks “how can this be consistent with the Congressional mandate the Fed is obligated to operate within?” we’d suggest, the only thing that might present a problem is its inherent common sense. Otherwise it shouldn’t be hard.

3 Replies to “Fed – the pause that nurtures the teenage bull”